give your mind

a new shift

this holiday

give your mind

a new shift

this holiday

BECOME

UNBEATABLE

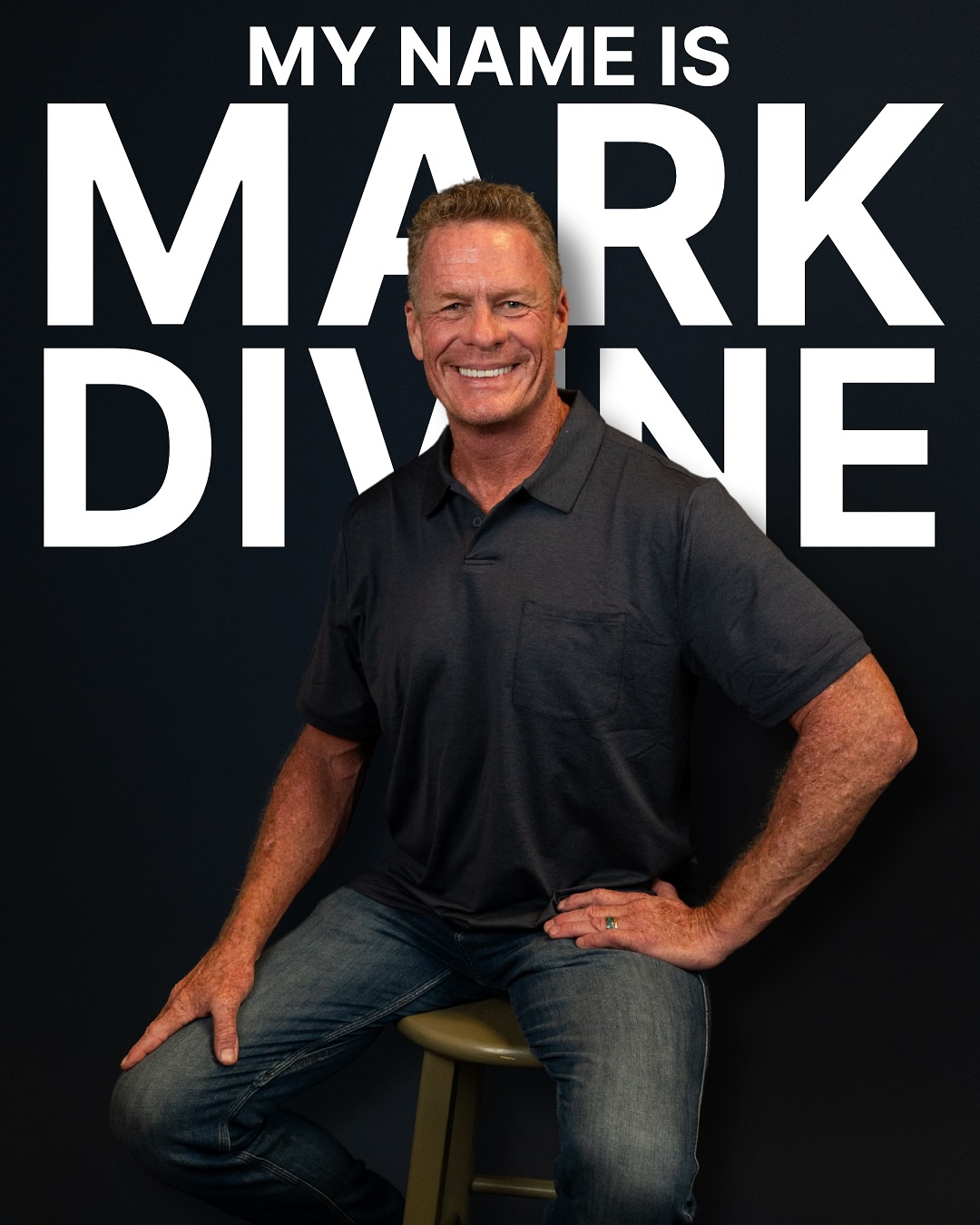

WITH MARK DIVINE

Upcoming Events

Join an Upcoming Event

Discover all events

Jan

10

Sept 8

LIVE VIRTUAL EVENT | MARK DIVINE

Unbeatable Leader Challenge

Three days of intensive mental training designed to forge unshakeable mental toughness and authentic leadership presence.

JAN

13

JAN 13 2026

LIVE VIRTUAL EVENT | MARK DIVINE

Unbeatable Leader Challenge

Two day of intensive mental training designed to forge unshakeable mental toughness and authentic leadership presence.

JAN

13

LIVE VIRTUAL EVENT | MARK DIVINE

Unbeatable Leader Challenge

Two day of intensive mental training designed to forge unshakeable mental toughness and authentic leadership presence.

Brands We Worked With

"The way you do anything is the way you do everything."

This isn't just personal development. This is elite leadership and warrior mindset training for mind, body, and spirt transformation.

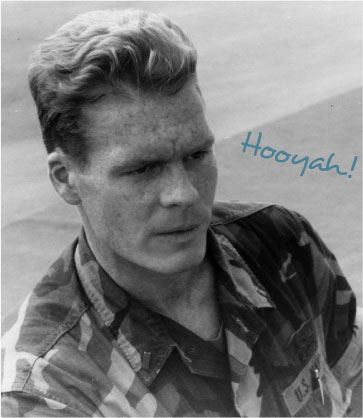

— Mark Divine, Ret. Navy SEAL Commander

Copyright © 2025 Mark Divine | All Rights Reserved